As the black stuff burnt in the UK plummets to a level not seen since the early steam age, we trace its long, deep history and the problems left in its wake

by Robin McKie

That invention helped to spark the Industrial Revolution and triggered a massive rise in annual coal use in Britain, which soared to well over 200 million tonnes by the mid-20th century. Now levels have plummeted back to their original pre-revolution state. King coal – once the undisputed ruler of British industry – has finally been dethroned.

It has been an extraordinary transformation. Britain evolved into a world power thanks to its use of coal. It was the first western nation to mine it and burn it on a large scale, and it was the first to fill its cities with polluted smog, factories and power plants as a result. Coal runs along a deep, dark vein through British history.

“For centuries, Britain led the world in coal production,” says Barbara Freese in her book about the dark stuff, Coal: A Human History. “It triggered the Industrial Revolution and created an industrial society the likes of which the world had never seen.”

Or, as George Orwell put it in his 1937 essay, Down the Mine: “Civilisation … is founded on coal. The machines that keep us alive, and the machines that make machines, are all directly or indirectly dependent upon coal.”

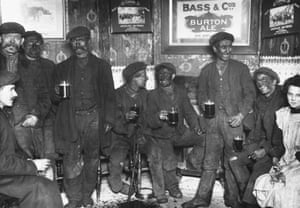

That was then, of course. Today, coal has long lost its lustre, to say the least. Its name evokes images of grimy poverty while its links to deadly air pollution, and its role in the dangerous overheating of our climate, have made it an increasingly unpopular source of energy in the UK. It provided Britain with enormous power but at an exorbitant cost in terms of pollution and the diseases – asthma, cancer, and heart and lung ailments – that emerged in its wake.Other countries – Germany, Poland, China among them – still burn coal in significant quantities. But the nation that first took advantage of it, and which built an empire using the industrial might it conferred, has now emphatically turned its back on coal.

“Coal use in the UK had been declining for some time but over the past few years it has dropped like a stone,” says Simon Evans of Carbon Brief, the climate change website. “Clean air acts, the end of steam trains, the rise of North Sea oil and of course increasing awareness of coal’s role in raising temperatures in the atmosphere have all played a part.

“However, the rate at which we have abandoned the use of coal over the past five years has been extraordinary,” adds Evans, whose analysis of coal use for Carbon Brief last week revealed its return to 18th-century levels. “In 2014, we used 84 million tonnes of coal. In 2019 that was down to 8 million tonnes. That is a drop of 84% in coal use in five years, and that is astonishing.” This meant only a handful of power plants still burned coal in the UK, and all of them were destined for closure in the next few years, he added.

During the Carboniferous period, plants covered the landscape, and when they died they formed layers of organic material in oxygen-poor swamps. First they were converted into peat, and then, after millions of years of deep burial, into coal, a combustible black rock containing traces of hydrogen, sulphur, oxygen and nitrogen.

Coal was burned in hearths and fireplaces in Roman times but it was not fully exploited until the 18th century, when improvements to the technology of steam engines saw them replace waterwheels, windmills and horses as the nation’s main providers of power. These refinements culminated in Watt’s invention of the separate condenser, which transformed the efficiency of steam engines and led to their widespread use in textile mills, mines and dozens of other heavy industries. Thousands of steam engines – all powered by burning coal – were installed across the country within a few years.

In the early 19th century, steam engines were further developed and used to transport goods and humans. Railways spread across the nation. Then, in 1882, Holborn viaduct power station, the world’s first coal-fired power plant, began to generate electricity for public use in London. Other cities followed suit. Coal was beginning to embed itself in the fabric of British life.

Over the years, coal continued to strengthen its grip on Britain, dampened only by disruptions such as miners’ strikes or the great depression, until, by the 1950s, the UK was utterly reliant on it for its energy and heating. Britons burned it in grates to heat their homes, shovelled it into the furnaces of huge generating plants to make electricity, made steel with it and used it as the fuel to run the nation’s railways – just as it had done for the previous 100 years.

But change was in the air. Yellow smog generated by coal fires hung over cities in increasingly thick blankets. This culminated in the great smog of London that enveloped the city for five days in December 1952, bringing life in the capital to a standstill while killing thousands from bronchitis, pneumonia and other respiratory illnesses in the process.

The Clean Air Act of 1956 was a direct response to the great smog. It encouraged householders to use other fuels – gas, electricity or less-polluting solid fuels – to heat their homes and stop using coal. Ironically, coal use reached around 210 million tonnes that year, its peak consumption over the past two centuries. That was also the year the UK established the world’s first civil nuclear programme, opening a nuclear power station at Windscale, in Cumbria. It would be downhill for Britain’s black gold from then on.

Next came the railways. In the 1960s, diesel and electric trains were introduced on the simple grounds that they were more efficient and far cleaner to operate. The end for steam came on 11 August in 1968, when the last mainline passenger train to be hauled by steam locomotive power left on an excursion from Liverpool to Carlisle and back.

Slowly, the need to burn coal to run British industry was being scaled down. The next watershed occurred in 1984, with the strike that brought defeat for the National Union of Mineworkers and triggered a series of widespread colliery closures across the country.

Then the UK electricity industry was privatised in the early 1990s, and the “dash for gas” began. Regulations limiting the burning of gas to make electricity were relaxed, and dozens of new power plants were built to turn North Sea gas into electricity, raising its share of UK electricity capacity from 5% to around 30%.

And finally, there has been the recent, extraordinary growth in renewable energy plants, including vast offshore windfarms, that now provide 37% of our electricity. They have provided the final, fatal blow to coal burning in this country, after 250 years.

“The challenge for the next few years is to get rid of coal completely, and then after that it will be to reduce the amount of gas that’s burned to make electricity in generators,” said Professor Keith Bell of the University of Strathclyde, co-director of the UK Energy Research Centre.

“We should look at last year as marking the beginning of the end for fossil fuels as sources of energy for electricity generation, and not before time.”