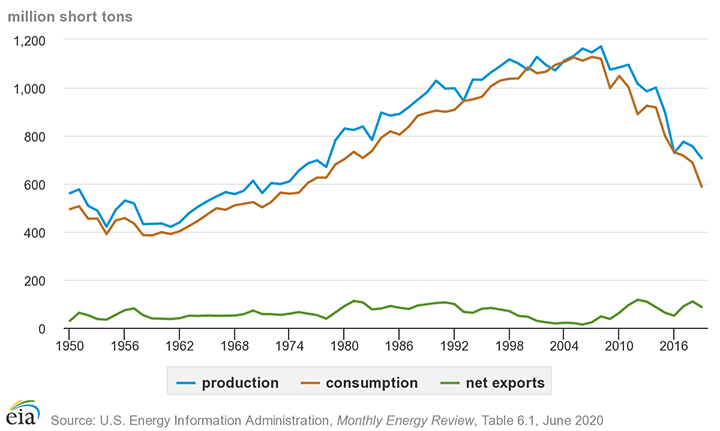

After serving as a primary source of electrical power generation for the last half-century, bankruptcies throughout the American coal mining industry in 2020 serve as the proverbial canary in the mine for the once dominant black nuggets found across the U.S. from the Appalachians to the Powder River Basin. While coal production is expected to increase globally—driven by demand growth in China and emerging markets—coal demand and production in the U.S. is forecast to continue its downward slide.

Exacerbated by the COVID pandemic, coal demand in the U.S. has fallen off an estimated 25% in 2020. Given the cheap prices for thermal coal assets, there will most likely be distressed merger and acquisition activity in the “Now.” With the ability to take a longer view of their investment than public filers, private equity firms have become more prevalent in acquisitions of coal assets.

Cheap Gas and Growth in Renewables Are Killing Coal

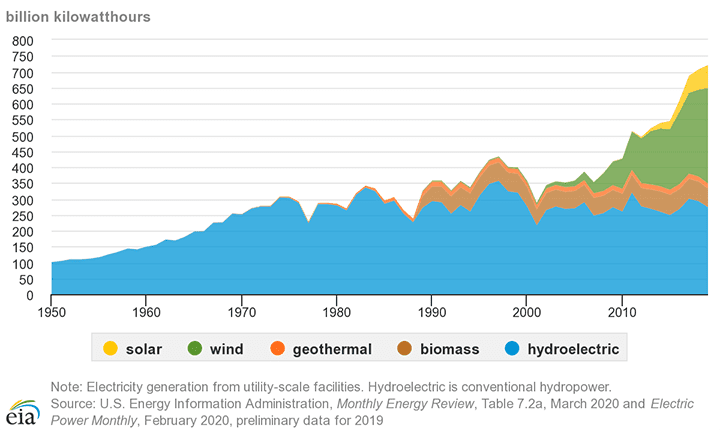

While much has been made of the potential for U.S. renewable power in the modern era and the prospect of a Green New Deal, renewables made up a greater percentage of U.S. electric power generation in 1950 than they do today. As shown in Figure 1 below from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the renewable energy of yesteryear (and today) was driven primarily by large-scale hydroelectric power. Future renewable energy projects, including wind and solar, are projected to make up a greater portion of the U.S. electric portfolio moving forward, spurred by government subsidies and advances in emerging technologies. While these technologies are quickly becoming cost-competitive with fossil fuels, they are not quite there yet.

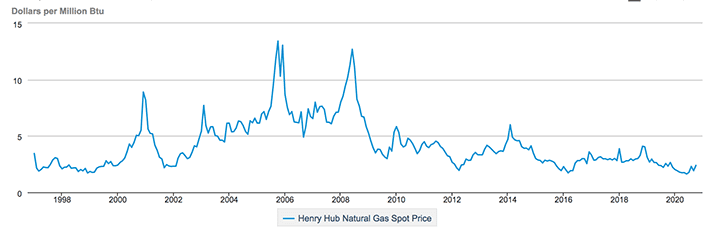

The shale revolution in the U.S. has unlocked a bounty of cheap, reliable natural gas that has become a bridge between the carbon-emitting coal of the past (Figure 2) and the promise of truly “clean” renewables in the future.

In most U.S. production basins, the goal of major exploration and production companies is to extract crude oil. The plentiful amount of natural gas that flows out of the formation is often considered a byproduct, and with pipeline capacity constraints and low prices for the resource, sometimes even a liability. To demonstrate the continued growth of natural gas supply on the continent, consider that approximately 5 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) of pipeline capacity was added in the U.S. in the first half of 2020 and continued expansion is expected.

Given the proliferation of natural gas in the U.S. market, it makes sense that an abundant resource at cheap prices would lead to a natural shift away from thermal coal. Prices for thermal coal have cratered during the COVID-19 pandemic, as less power generation has been necessary across the country. The novel coronavirus could explain a drop in pricing for both coal and its fossil fuel brethren; yet, before the pandemic, natural gas remained an absurdly cheap commodity in the U.S. market as shown in Figure 3 below.

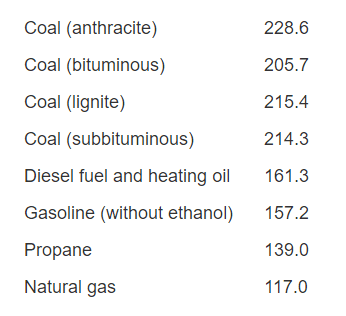

Cheap supply of feedstock is one thing, but even more challenging to the incumbent champion thermal coal are the environmental benefits offered by natural gas. Natural gas-fired power plants emit approximately 50% less CO2 (the primary culprit in climate change) than new coal-fired plants, as shown in Figure 4 below from the EIA as of June 2020.

Companies, Including Banks, Are Abandoning Coal

Shifts in the social and political climate in the U.S. over the last decade have brought the preservation of the literal climate to the forefront. Major energy producers (including all of the supermajors) have gone on record saying they intend to limit their carbon emissions moving forward, not only through the implementation of long-term renewable energy goals, but also the retirement of existing coal-fired power plants (and pledges to eliminate construction of new coal-fired power in the future).

Duke Energy is among the power generation companies to make the commitment to have net-zero emissions by 2050. CEO Lynn Good in Duke’s net-zero press release indicated a “diverse mix of renewables, nuclear, natural gas, hydro and energy efficiency are all part of this vision.” Other major power producers have followed suit, pledging to substantially reduce, if not eliminate entirely, carbon emissions over the coming decades.

A big part of the problem with coal as a sector is debt and time. In a prolonged trough, the sector has become over-leveraged at what might otherwise be considered very attractive borrowing rates. With demand declines and commodity price decreases weighing on the companies in the space, debt service is simply not sustainable. The industry went through a wave of bankruptcies in 2015–2016. Even more problematic for the coal industry has been a loss of future debt funding and support from nearly all of the major U.S. banks.

JP Morgan plans to phase out all loans to companies that get the majority of their revenue from thermal coal mining by 2024. Citi plans to stop providing underwriting and advisory services to thermal coal mining companies by 2025, and eliminate exposure entirely by 2030. Morgan Stanley has said it will “decline financing transactions globally that directly support the development or physical expansion of coal-fired projects unless carbon capture and storage or equivalent carbon emissions technology is involved.” A decline in end markets, coupled with a severe decrease in the availability of funding for expansion, has dealt a one-two punch to the industry as a whole.

World Markets Offer Little Hope for Domestic Miners

For a commodity asset such as coal, non-American end markets are largely unavailable as a viable long-term solution to make up the difference. Historically, only 10% to 15% of U.S. coal production has been sent to export markets (12% in 2019) and more than half of this was metallurgical coal.

While developing economies, such as China and India, respectively the first and third-largest producers of electric power, continue to construct coal-fired power plants due to less stringent environmental regulations, their input needs are largely served by resource deposits located closer to their respective geographic markets. The elimination of restrictions on U.S. oil and gas exports has led to the development of several large-scale natural gas liquids (NGL) projects that will export America’s cheap natural gas to compete with coal for power production abroad moving forward (Figure 5).

The glory days of U.S. coal mining, as we once knew them, are over. A prime example is Murray Energy—previously the largest privately owned coal mining firm in the U.S. Murray emerged from bankruptcy in September 2020 after writing off close to $8 billion in debt. Blackhawk, Blackjewel, Cambrian, Cloud Peak, Piney Woods, and Trinity have all filed for bankruptcy in 2020.

For publicly traded companies in the mining space, trading multiples have cratered over the last five years, with some of the largest players trading at an anemic multiple of about 1x revenue and less than 2x EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). Many distressed or bankrupt coal businesses have been acquired for metallurgical reserves by merely taking over thermal coal environmental asset retirement obligation liabilities. Even while using this low-cost acquisition model, companies like American Resources Corp. are struggling, with plunging share prices amidst the pandemic.

Coal mining will continue to exist in the U.S. out of necessity, if only to serve the metallurgical market, for which there is no alternative to coking coal. Coking coal makes up about 10% of domestic coal production annually. In terms of “Next,” thermal coal will remain a part of the U.S.’s energy infrastructure in the immediate future, while the remaining portion of the coal-fired power facilities in the country’s portfolio phases out. However, it will be replaced by natural gas in the near term and true renewable energy in the long run.

Like its placement in Christmas lore, coal has been relegated to the naughty list in American energy generation. We are witnessing the poignant end of a once-dominant American industry—continued consolidation of mining companies and bankruptcies for those still subject to any meaningful leverage—as the U.S. moves forward using cheaper and greener alternatives.

The decline in the coal industry should also serve as a warning bell to companies operating in the broader fossil fuels space. Historically, coal companies were not prohibited from diversifying their assets and acquiring natural gas reserves or other companies. Yet, very few players in the coal segment truly broadened their operations, leading to their demise along with the resource to which they tethered themselves. Continued pushes toward sustainable energy and cleaner alternatives in developed markets will create a need for the dominant fossil fuel companies of the past to change their modus operandi to survive.

—Joe Mease is a Strategy and Transactions Director at Grant Thornton LLP, and Bryan Benoit is the U.S. National Managing Partner, Energy and Global Valuation Co-Head at Grant Thornton LLP.