A drive through Montana’s coal country starts at the Little Bighorn Battlefield and ends in an uncertain future.

The road rolls over prairie grasslands of the Crow Indian Reservation, just south of the Absaloka coal mine. Then it climbs the Wolf Mountains and crosses into the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation amid tumbling sandstone formations tipped with scoria, a clay formation toasted red by prehistoric burning in underground coal seams. At Lame Deer, the road bends northeast through hills cut by Rosebud Creek, until suddenly coming over a rise to reveal the four smokestacks of Colstrip’s coal-fired power plant.

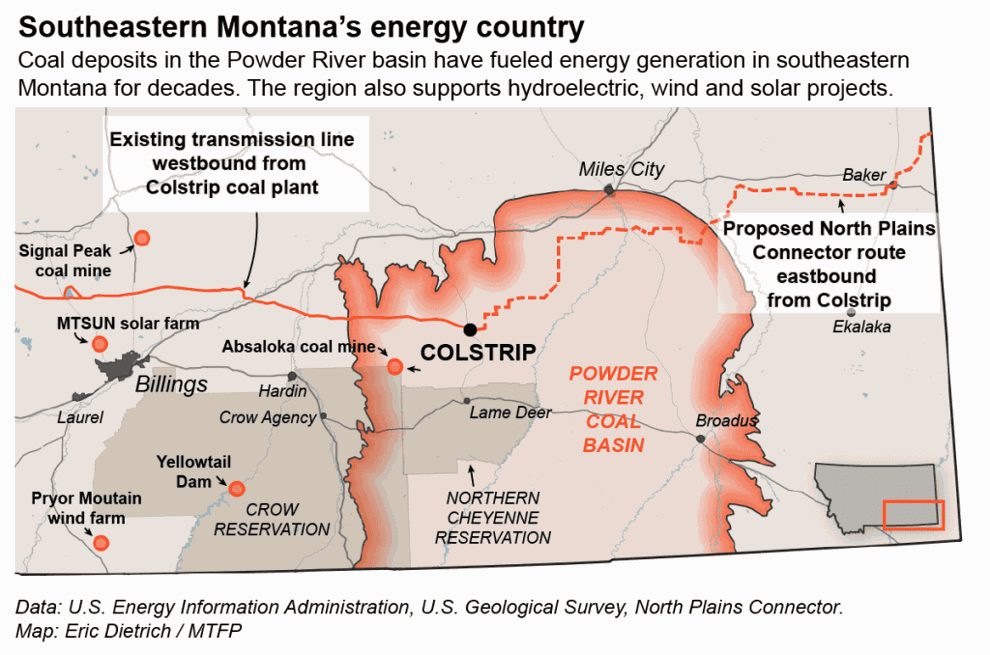

It’s harder to see the actual coal unless you’re in an airplane. The strip mines between Colstrip and Crow Agency expose long black beds of burnable carbon. From this northern edge of the Powder River Basin south into central Wyoming lies 41% of the United States’ coal supply. For the past century, it has fed the nation’s energy demand.

Nearly all that demand has vanished. The Absaloka coal mine on the Crow Reservation lost its last utility customer last year. Colstrip’s power generating plant is losing utility customers as public utilities switch over to renewable energy sources such as wind and solar.

A switch to renewable energy could happen here, too. Tens of billions of federal and private dollars stand ready to reshape Montana’s coal country, if its residents choose a path forward. Three communities central to the region’s identity — Crow, Northern Cheyenne and Colstrip — have remarkably different attitudes toward that future.

That leaves some big choices for people in Montana’s coal country. The decisions they make will be refracted through economic forces beyond their control, as well as cultural and traditional perspectives that define what it means to live in coal country. And as this 2024 election year winds to a close, those residents can make their opinions known through their votes on races from tribal council seats to the White House.

Same view, different visions

Where someone stands on the future of Montana’s coal industry depends on where they sleep.

Although their 444,000-acre reservation has 23 billion tons of proven reserves, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe has declined to exploit its coal. Many tribal members work at Colstrip’s mines or power plant. But they have rejected past proposals for developing industrial-scale coal operations on the reservation.

But the impact of the nation’s ongoing energy transition has been much greater — nearly 1,000 jobs connected to the Crow tribal government have also lost their coal royalty revenue stream since 2017. While much of Indian Country in Montana has been a Democratic voting bloc, the Crow have ties with Republican Sen. Steve Daines, who has pushed a bill in Congress to give the tribe an option to share royalties from the Signal Peak coal mine just north of the 2.2 million-acre Crow Reservation through a mineral rights swap.

In Colstrip, decades of political influence has kept the state government focused on keeping the traditional coal industry viable. That’s produced beneficial rulings at the Public Service Commission for NorthWestern Energy to keep coal in its portfolio, provided economic transition programs, and stalled efforts to develop renewable energy projects that might replace coal.

Those alternatives run the buffet line from $43.7 million for rooftop solar panels on private homes in tribal, low-income and economically distressed parts of Montana to a $700 million federal contribution to a $3.2 billion transmission line project that could link wind energy producers from North Dakota to Oregon.

To spur more development, the federal Energy Infrastructure Reinvestment Program has $5 billion in direct loan authority backed by $250 billion in loan guarantees. Fleshing out the federal investments are tax incentives for renewable energy programs, infrastructure grants for building projects, job training for new industries and remediation funds to clean up old coal mines.

If it all gets spent, the federal bill could cost $1 trillion. The Biden White House estimates that the benefits will total more than $5 trillion in worldwide ecological and economic benefits by 2050.

But people all across coal country don’t appear to be lining up for the next new thing.

For a variety of reasons, the federal spending opportunities have had difficulty getting attention. Part of that stems from the long allegiance to coal as a source of jobs, purpose and identity. Part comes from distrust or unfamiliarity with new technology. And perhaps some signifies a defense against the sheer blizzard of controversy surrounding global warming, economic upheaval, Indigenous/white culture friction and plain old change.

The landscape itself doesn’t offer many hints at a future direction. The massive Yellowtail hydroelectric dam on the Bighorn River would remain, but without coal, not much else points toward an economic future. Southeast Montana is not among the state’s most productive farming or cattle acreage. It lacks the tourist magnetism of the western part of the state. Any industrial production would face miles of transport expenses to reach a distribution hub like Billings. As is, about 60% of the price Pacific Coast power plants pay for Montana coal goes to cover the railroad shipping expense.

And while the wind blows hard and the sun shines bright across this bit of Montana, renewable energy doesn’t appear to offer the same community impact that a climate-cooking coal mine does. As one Northern Cheyenne resident put it: “Ever seen a wind farm with a parking lot?”

Tribal perspectives

Jason Small made that observation over a piece of coffee cake on the patio of the Custer Battlefield Trading Post, just across Highway 212 from the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. That day he was wearing a sleeveless T-shirt and overalls, on his way to a boiler repair job in Helena. On different days, he’d be in a suit and tie as a Republican legislator representing Busby and the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation. He also wears the hat of the executive secretary for the Montana AFL-CIO, the state’s biggest union network.

“There’s night-and-day differences between the two tribes,” Small said of the Northern Cheyenne and Crow. “Energy policy, politics, climate, everything. The Crow opened their mine in 1974, and it was putting $50 million, $60 million a year into their budget in the Obama years. On Northern Cheyenne, the traditional people didn’t want to mine coal. There was a popular vote, and everyone decided to leave it alone.”

The corporations developing the coal paid high wages for hard work, averaging $75,000 a year. They also provided scholarships for kids to go to college or get job training. The royalties from state coal severance taxes flow back to local governments in lieu of local mill levies, or come back circuitously through the Montana Coal Tax Trust Fund. In 2023, that fund (enshrined in the state Constitution) held about $1 billion. However, by 2024, Montana tax collectors were receiving more from cigarette sales than from coal royalties.

“People don’t want to lose the opportunities they have,” Small said. “Something new comes along, they don’t want to take a step backward.”

But coal may not be able to take a step forward.

Can coal compete?

Next to the long, straight seams of coal currently under excavation west of Colstrip, an observer can see a smaller series of gouges in the earth that look a little like a Wi-Fi symbol. Those are the revegetated remains of Northern Pacific Railroad coal mines from the turn of the 20th century, when this part of Montana started playing a part in the nation’s industrial development.

Montana’s coal took an even more prominent role in the 1970s, after scientists confirmed the link between the more sulphureous Appalachian coal and acid rain, which was poisoning lakes across the eastern United States. The subbituminous coal of the Powder River Basin doesn’t generate as much heat when burned as the bituminous coal of West Virginia, but its exhaust has less sulphuric acid.

Although Montana encloses most of the Powder River Basin deposit, Wyoming digs much more of that coal — 244 million tons in 2022. Montana added about 30 million tons that year, despite sitting on 74 billion tons of recoverable reserves stretching from Wyoming to the Canadian border.

Nevertheless, coal of either type produced the single greatest amount of greenhouse gases driving up global temperatures. Oil company researchers in the 1970s connected the dots between burning fossil fuels and global warming. But those same companies, including ExxonMobil, mounted decades of counter-campaigns disputing the danger of climate change while burying their own science.

Growing awareness of climate-change impacts such as longer wildfire seasons and shorter ski seasons led to global social pressure to move away from fossil fuel burning. That included decisions by Colstrip power clients such as Puget Sound Energy and Avista Corp. to drop their investments in Montana coal in 2025. Those moves were prompted by state law changes in Oregon and Washington requiring the states’ energy utilities to seek greener energy sources.

At the same time, other market forces undercut coal’s economics. Methane, commonly known as natural gas, costs around 6 cents a kilowatt hour, while coal-fired electricity costs upwards of 14 cents. Both fossil fuels face growing opposition because their burning warms the atmosphere, scrambling planetary weather patterns and intensifying natural disasters like hurricanes and wildfires.

A wind farm can generate power for 3 to 6 cents per kilowatt hour. The Pryor Mountain wind farm just south of Crow Agency produces 240 megawatts of power at around 5 cents per kilowatt. An 800-acre solar farm on the Billings rims adds another 80 megawatts.

A megawatt of electricity powers about 800 homes in the northwest United States. Renewable energy sources are becoming more affordable and reliable. In September, wind and solar generators in the four-state region that covers Colstrip produced 6.6 gigawatts of electricity, while coal facilities in the same region produced 7.1 gigawatts.

For its part, Colstrip generated only half its 1.4-gigawatt capacity on 12 days of that month. Whereas wind and solar had only 14 hours when they produced less than Colstrip’s full potential. In other words, even when the wind wasn’t blowing or the sun shining, wind and solar out-generated Colstrip’s coal furnaces.

Money and votes

Incumbent U.S. Sen. Jon Tester, a three-term Democrat, was part of the final negotiating team that produced the bipartisan Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure and Jobs Act — legislation offering billions of federal dollars for investment in coal country. Tester’s Republican challenger, political newcomer Tim Sheehy, was recruited by Sen. Steve Daines and the National Republican Senatorial Committee Daines chairs. National polling shows Montana’s Senate race “leaning Republican.”

That makes getting the attention of Indian Country essential to both candidates. Native Americans make up about 7% of Montana’s million residents — the only demographically significant minority in an otherwise overwhelmingly white state. But while voter turnout for tribal elections tends to be strong on reservations, that hasn’t translated to predictable results in state and federal races. And although Native Americans nationally tend to vote Democratic, tribal differences such as those seen on the Crow and Northern Cheyenne reservations make the voting bloc murky.

Colstrip has been a Republican stronghold for decades, as have most of the surrounding counties. As president, Republican Donald Trump promised to “bring back coal.” However, his administration saw the closure of 75 coal-fired power plants and the loss of about 13,000 coal jobs nationally. In Montana that included the closure of Colstrip Units 1 and 2, the Decker mine, the Lewis and Clark Generating Station in Sidney and the Savage mine. It also included the bankruptcies of Westmoreland, Cloud Peak, Lighthouse and Talen.

Democratic President Joe Biden has actively supported unions and the heavy infrastructure spending that are trying to bring renewable energy projects and dollars to Montana’s coal country. But he also imposed new air pollution regulations that NorthWestern Energy officials claim will force premature closure of Colstrip. On Oct. 4, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to block Biden’s rules.

Many of those economic and political forces will play out within the next year. The election takes place Nov. 5. In his City Hall office, recently rebuilt with local coal revenue, Colstrip Mayor John Williams said the changes can’t be ignored.

“We don’t want to be defined by the stacks,” Williams said, referring to the four landmark exhaust towers of Colstrip’s generating station. “We’re more than that.”