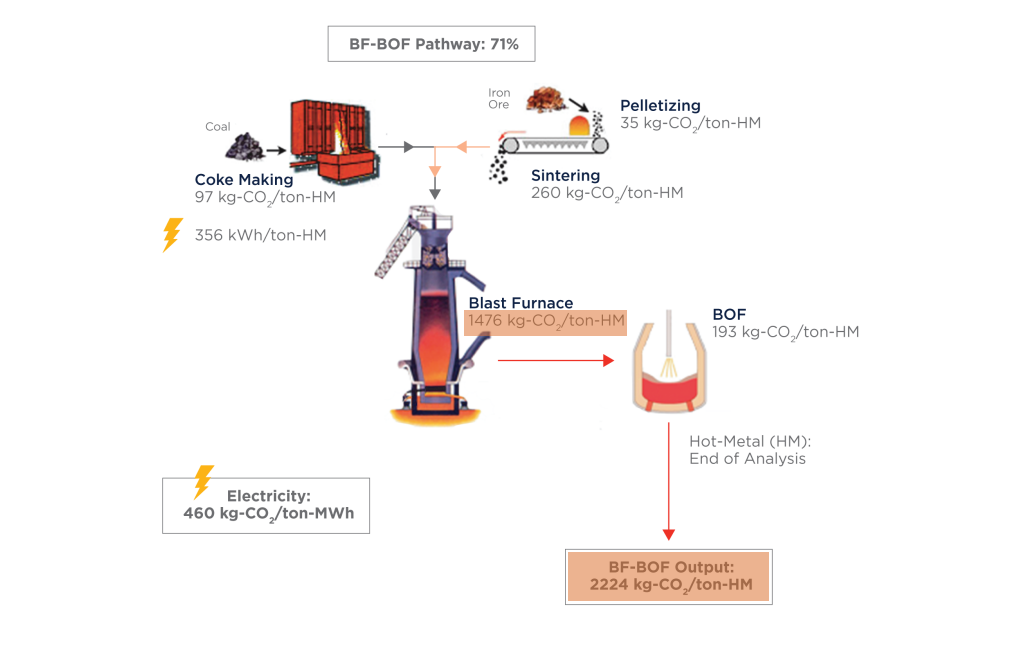

Steel is the building block of modern society, underpinning a wide range of essential industries. From construction and infrastructure to cellular towers and electronics, steel is indispensable in almost any activity in everyday life. However, it is a particularly ‘hard-to-abate’ sector due to the high emissions involved in the traditional methods of steelmaking. Manufacturing alone contributes between 6-7 percent of global emissions and upwards of 8 percent of energy-related emissions globally. This poses a serious threat to the environment, as reducing emissions in this sector requires significant investment, technological innovation, and a complicated transition to alternative methods. Currently, the blast furnace to basic oxygen furnace method (BF-BOF) still dominates production, accounting for over 71 percent of all steel manufacturing. BF-BOF is significantly dependent on coal or coke, which results in dangerously high levels of CO2 emissions.

Source: Columbia SIPA, based on data from World Steel Association

Electric Arc Furnaces (EAFs) are a popular alternative, where recycled scrap steel can be utilised to produce high-grade steel without coal. This method is suitable for countries with low iron ore deposits. However, for large producers of iron ore like India, scrap steel-based EAFs are not as desirable. EAF can also use the products of direct reduction of iron (DRI) and pig iron to increase efficiency; DRI is equally pure as pig iron but has a lower melting point and thereby consumes less energy. India is a leading producer of DRI but primarily uses coal as feedstock.

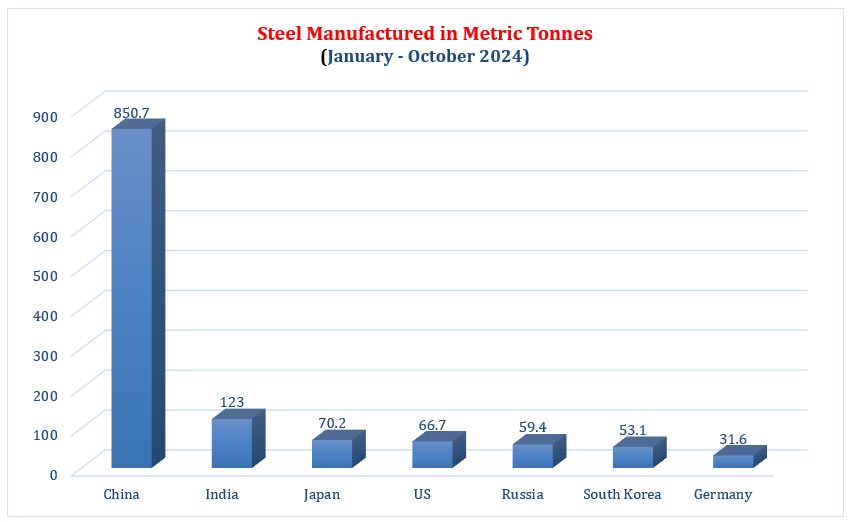

China’s overcapacity for steel manufacturing casts an ominous shadow on the rest of the world, emphasising the need to build supply chain resilience at the forefront.

Conversations around greener steel emerged due to the need to transition to sustainable manufacturing. The implications of carbon pricing mechanisms will drive up the production costs of grey steel. The urgent need to reduce emissions, more importantly, is crucial in addressing the climate crisis before the point of no return. Moreover, steel can serve as a pathway towards broader discussions about ‘hard-to-abate’ industries. These discussions demonstrate a collective willingness to begin a challenging shift in the industry.

Growing geopolitical concerns are also driving the willingness to transition to sustainable steelmaking in various parts of the world. China’s overcapacity for steel manufacturing casts an ominous shadow on the rest of the world, emphasising the need to build supply chain resilience at the forefront. This concern is more acutely felt in the Indo-Pacific, which has not been eased by the implications of tariffs being imposed by the United States (US) in the ongoing trade war. This has accelerated the sense of urgency around the region to decarbonise, scale up climate action, and adapt to American ambivalence towards phasing out green manufacturing.

Visualisation by Author; Data Source: Wordsteel Association:

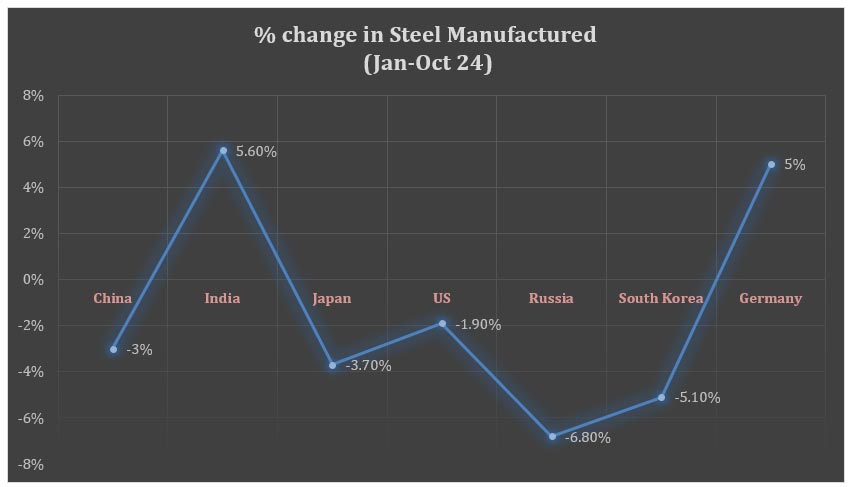

Visualisation by Author; Data Source: Wordsteel Association:

The rate of growth in the steel manufacturing capacity in India is unparalleled, both in terms of volume and proportionality. It remains evident, though, that the world’s dependence on China can quickly be used as leverage. As nations grow wary of this threat, India is undoubtedly the closest competitor. However, the current trajectory won’t result in a meaningful shift unless there is a swift transition to more sustainable methods. Attempting to compete with China’s steel manufacturing capacity by using high-emission technology is nearly impossible; it continues to show no reluctance in the usage of coal and iron ore, which it has in abundance.

The prohibitively high costs of green H2 can only be addressed by scaling to bring down costs to make it a competitive method of production following the implementation of carbon taxes in the coming decade.

The most prominent development in steelmaking has been around green hydrogen (H2) as opposed to the traditional BF-BOF method. The significance of green hydrogen has been previously illustrated. The prohibitively high costs of green H2 can only be addressed by scaling to bring down costs to make it a competitive method of production following the implementation of carbon taxes in the coming decade.

An Eastward Shift in Indo-Pacific Leadership

The landscape matrix of the Indo-Pacific region is shifting. In the absence of the US, other major actors in the Indo-Pacific region are keen to persist in their decarbonisation efforts, uninterrupted by changes in political leadership. While other nations scramble to forge plurilateral paths as the notion of multilateralism fades away, emerging Asian powers have already realised the necessity for immediate action. These initiatives must come from proactive groupings of governments and businesses to survive amidst a volatile geopolitical climate.

Through plurilateral cooperation, sustainable alternatives to grey steel can circumvent supply chain overdependence and regulatory challenges. Joint initiatives from the emerging Asian leadership, spearheaded by India, Japan, and South Korea, can restore competitiveness and lead to a much-needed reduction in terms of environmental impact. South Korea’s involvement in these discussions must also be a high priority; proportionately, emissions from the South Korean steel industry are nearly double the global average—16.7 percent of all national emissions and 40 percent of industrial GHG emissions.

With India set to finalise carbon trading deals with Japan and Singapore in 2025, this will provide a strong foundation to make green steel competitive and incentivise investment. India and Japan also held bilateral discussions in July 2024 to accelerate the transition to sustainable steelmaking. GR Japan also hosted an event in October 2024, bringing together key actors in the battery and green steel sectors from both countries.

India and Japan also held bilateral discussions in July 2024 to accelerate the transition to sustainable steelmaking.

While sustainable steelmaking scales up and becomes more affordable, domestic policymakers should also apply subsidies to green steel production. To meet demand for green steel, which is projected to rise exponentially, subsidies are essential, as is the norm in the industry, even for grey steel. India must further address the lack of existing technology and investment in the R&D of green steel. Relevant actors from the Japanese government and industry leaders will have key roles to play in transferring equipment, knowledge, and investment into emerging sustainable technologies in India. This would not only strengthen Indo-Japanese trade relations but also build resilience in the Indo-Pacific and further cement their roles as leaders of the region.

Multiple domestic and external factors also increase the urgency for India to accelerate sustainable steelmaking. While India is a leading producer of crude steel, between April 2024 and January 2025, Indian imports of finished steel products from China, South Korea, and Japan hit a record high. Vietnamese overcapacity may spill over to India at lower prices, adversely impacting the Indian steel industry. Keeping these challenges in mind, domestically, the existing model of the steel industry should be re-evaluated. India currently levies an export duty of 30 percent on high-grade iron ore, which is typically tax-free among leading manufacturers worldwide.

Enhancing Indo-Japanese Trade and Cooperation

As India and Japan take initiatives to accelerate the transition to sustainable steel and the use of green hydrogen, cooperation between governments and industry will be invaluable. South Korea’s political uncertainty and high levels of steel-related emissions need to be internally addressed so it can meaningfully contribute to initiatives in this Asian triumvirate. In the meantime, developing bilateral ties will be instrumental in implementing pilot projects of new green technologies.

Japanese shipment of steel manufacturing equipment was withheld at a port in India following a communication breakdown.

Policy recommendations in this context must be centred around how India and Japan can take advantage of the carbon credit trading agreements to facilitate cooperation between industry and government from both countries. Industrial cooperation will be particularly essential for the development of project preparation capacity. Governments will also play a key role in enacting policy to encourage joint ventures (JVs) and public-private partnerships (PPPs). Japan has reportedly sought an exemption from India’s steel import tariffs, which Indian policymakers should carefully consider to strengthen their partnership.

Additionally, regulatory mechanisms to monitor progress on sustainability goals in steelmaking and green hydrogen initiatives should be established to uphold corporate accountability and transparency. Furthermore, governments should seek to improve their customs procedures to expedite the import and export of materials. Japanese shipment of steel manufacturing equipment was withheld at a port in India following a communication breakdown. Digitisation of customs procedures to reduce delays and enhance transparency.

Establishing a working group, which includes both government and corporate actors, will be key. This should be designed to enhance cooperation and incentivise innovation to drive decarbonisation efforts in the Indo-Pacific. More structured interaction between policymakers and investors in the steel sector in the Indo-Pacific will help solidify the new Asian leadership in the region.