A photograph in the entrance hall at Komati Power Station shows the plant in better times, its nine generating units belching steam and smoke into the night sky.

Those days are never coming back: Komati’s sole remaining working unit is facing closure within two years under plans by state power utility Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd. to shut about a quarter of its coal-fired capacity by 2030. Next door at the Goedehoop mine, arrays of solar panels line the main access road, a sign of what may be to come for South Africa’s coal belt.

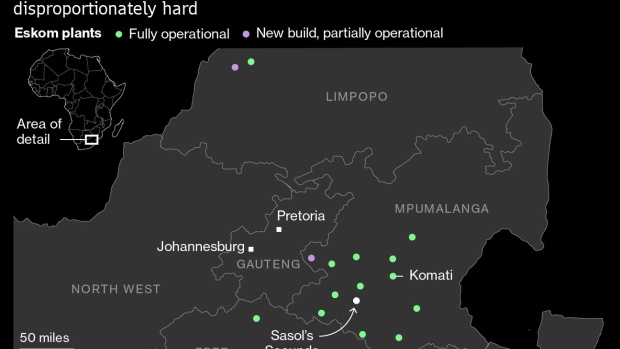

For decades, almost all the electricity needed to power Africa’s most industrialized economy has been produced by a fleet of aging coal-fired plants constructed alongside the mines to the east of Johannesburg. That’s made the province of Mpumalanga, in which Komati is located, one of the most coal-dependent and polluted regions on Earth.

Decommissioning those plants is essential if President Cyril Ramaphosa is to meet a commitment to reach net-zero carbon-dioxide emissions by 2050, and yet the closures also put tens of thousands of jobs at risk. Potentially destabilizing anywhere, in South Africa it’s a recipe for dangerous economic and political upheaval that’s prompted the government and industry to sign on to the concept of a “just energy transition”—an attempt to create new employment and win public buy-in for the impending change.

“If you look at some of these communities, they have been dependent on the power station and, in some cases, mining for many many decades, generations,” said Mandy Rambharos, head of Eskom’s Just Energy Transition office. “You can’t just lock the door, throw away the keys and walk away.”

South Africa’s current plans are still “highly insufficient” to help meet global climate goals, according to Climate Action Tracker, which provides independent scientific analysis. And with South Africa yet to submit an updated set of climate commitments ahead of the United Nations COP26 summit in the Scottish city of Glasgow in November, the government is under pressure to set more ambitious goals.

Read More From Bloomberg Green’s Series on Hitting Net Zero by 2050

The lack of certainty over the future is unsettling for those on the front line who must shoulder the burden of change.

They include Cathy Mkhuma, who was born in Komati and now represents it as a local government councilor for the ruling African National Congress. Mkhuma, 36, has witnessed the town’s demise up close: Her father worked as a gardener for Eskom, which started generating electricity in the town in 1961.

In that time, “it has changed from best to worst,” she said as she stood next to a drab community library, across the road from abandoned sports facilities that Eskom once paid for. “There’s nothing left.”

South Africa’s challenge in filling that void is one that’s confronting coal belts from Pennsylvania to Poland, China and Australia as pressure increases to eradicate a fossil fuel that is the single biggest contributor to global climate change. While the economic and environmental logic points to the shift away from coal, the political will to make it happen can be harder to summon because of the need to mitigate the impact of job losses, or suffer the consequences at the ballot box in democracies.

In eastern Europe, governments that have until recently been unwilling to address climate change have begun to shift their policy stance to cut carbon emissions, in part to capture youth votes or to blunt political opponents, but also in response to relentless corporate pressure that links money to climate policies.

Take Poland, which if you exclude Germany generated more energy from coal than the rest of the European Union combined in the first half of last year. The government courted anger last year in the coal-producing region of Silesia by negotiating a deal with unions to exit the fuel entirely by 2049. Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki justified the move saying the energy transition was inevitable. “What we want is for this process to be just,” he said.

Spain stands out as a rare example of doing it right, albeit with a far smaller mining sector. In 2018, its government struck a deal with the miners’ union that would see an investment of 250 million euros ($303 million) go to the affected regions over the next 10 years, showing that it’s politically possible to do right by workers while rushing to meet climate goals.

In India, the world’s third-biggest carbon emitter, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government is under pressure to meet China’s commitment to net zero emissions by 2060 with its own target. Yet doing so would require an overhaul of its development aims to put climate change on a par with infrastructure building, a move that would require institutional changes, according to Ajay Mathur, chairman of the Energy Research Institute in New Delhi. “And institutional changes take time because you need to address concerns of those who lose,” he said.

South Africa’s future losers are clear; how to address their concerns less so. Some municipalities in Mpumalanga depend on coal for more than 40% of their economic activity. Coal mining earned the country 139 billion rand ($9.6 billion) in 2019 and employed over 92,000 people, according to the Minerals Council South Africa. With many banks now refusing to finance new coal projects, Eskom has plans to convert some plants into renewable energy facilities, install gas turbines and create industrial zones. The problem is all of the plans cost money and Eskom has none: it is 464 billion rand in debt.

Still, the global appetite for “green finance” to fund renewable projects and socio-economic initiatives to lessen the impact of closures offers one possibility. Eskom’s Rambharos said the utility has received a number of letters of interest from development finance institutions.

A little south of Komati, Sasol Ltd. owns the vast Secunda plant, which employs some 22,000 people turning coal into gasoline and petrochemicals, producing more harmful emissions than the entire output of some oil companies. Sasol aims to use more power from clean energy and eventually switch to natural gas in the 2030s then ultimately hydrogen. Yet South Africa has little gas infrastructure in the form of pipelines or liquefied natural gas terminals, showing the lack of coordination over the energy switch.

“We have to be cognizant of the fact that we do operate in a South African economy with no gas infrastructure right now and no big renewable power,” said Shamini Harrington, vice president for climate change at Sasol.

Political considerations are another hurdle to be overcome. Mine unions and mining have always been core to African National Congress support: Ramaphosa founded the National Union of Mineworkers, the biggest union at Eskom, while Minerals & Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe is a former secretary general of the union who once headed a branch of the organization in the coal belt. Both are reliant on labor support to keep them in power, and Mpumalanga’s municipal councils and provincial government are firmly in the hands of the ruling party.

Mixed messages from government add to the confusion. While Ramaphosa regularly touts the potential of renewables, Mantashe stresses that a just transition must be gradual and that a significant role should be maintained for nuclear and “clean coal,” which would mean investing in technologies to use coal without the carbon impact.

For many, the only certainty is the approaching deadline for plants to be decommissioned.

“People will be losing jobs, for the community there are shops and accommodation that will suffer,” David Fankomo, a NUM official, said in a boardroom at Komati. As yet, there have been no discussions on what will replace the station when it goes, he said.

What comes next is the subject of talks at executive level with the help of consultants, but plant and mine workers are largely in the dark, as are the communities they live in.

“We are just waiting to see what happens,” said Mkhuma, the Komati councilor.