As Germany moves away from fossil fuels towards a clean energy economy, the east German state of Saxony-Anhalt is undergoing its own structural shift away from the lignite mining industry it has depended on for decades. “The state is dealing with structural economic changes caused by the coal exit, as well as demographic changes: young, higher-educated people are leaving the state and moving to big cities,” political scientist Michael Böcher from the University of Magdeburg in Saxony-Anhalt’s capital tells Clean Energy Wire.

Saxony-Anhalt has only a little over two million citizens — barely more than the city of Hamburg. The state is one of the poorest and its population is older than the national average, making it hard to draw comparisons with the federal level. Yet, the election highlights the political issues at play in the midst of the German energy transition. “Saxony-Anhalt is a very good example of the general conflicts we have to overcome on our way to climate neutrality,” says Böcher. “There are people who benefit from the transition and are hopeful about it, and there are those who fear change, who are scared of losing their jobs and their prospects. I think we will have similar conflicts all across Germany, but it can already be seen in Saxony-Anhalt.”

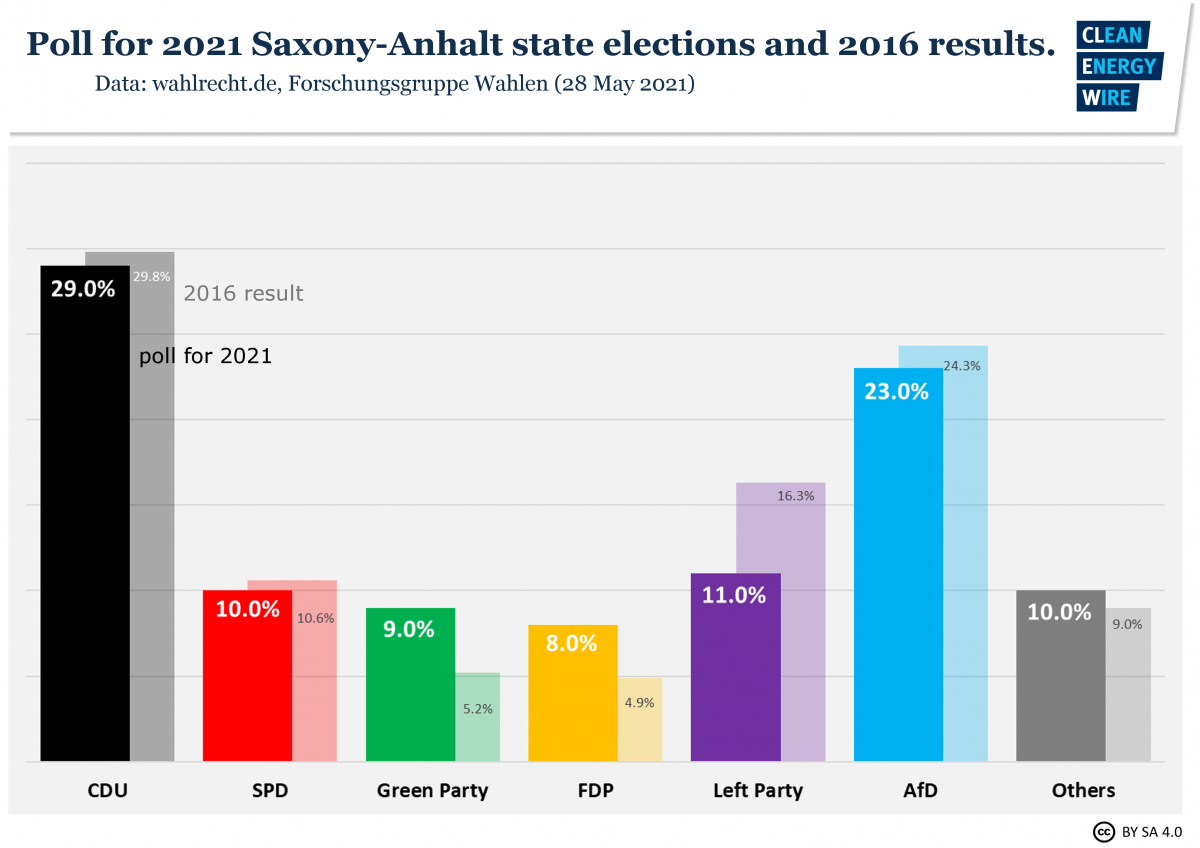

On Sunday 6 June, voters in Saxony-Anhalt will head to the ballot box to elect a new state government. The state is currently governed by the CDU, the Social Democrats (SPD) and the Green Party, making up a so-called “Kenya coalition” — referring to the party colours black, red and green, which make up the Kenyan flag — under the leadership of CDU minister president Reiner Haseloff. Recent polls show the CDU is leading with around 29 percent of the vote, followed closely by the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) with around 23 percent. As all parties rule out a coalition with the AfD, a repeat of the previous government – possibly with the addition of the pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) – is a likely election outcome.

The Saxony-Anhalt state election is a last test before the federal election on 26 September, when German voters will pick a new federal government, including a new chancellor to succeed Merkel. In Berlin, the Thuringia and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania state elections will take place on the same day.

One of Germany’s three main lignite mining regions called the Mitteldeutsches Revier, or Central German Mining District, is located in Saxony-Anhalt and the neighbouring state of Saxony. The mining district employs around 2,200 people directly, according to data from the Federal Association for Lignite (DEBRIV) from 2020. After Germany decided to phase out coal by 2038, the state ensured 4.8 billion euros in structural financial support to finance the transition in the coming years. The region wants to invest in high-tech innovation and research, but no concrete plans have been prepared yet.

CDU leader Haseloff wants to promote above all the development of alternative fuels and the production of green hydrogen. “We need new technologies,” said the prime minister in an interview with regional broadcaster MDR. Only if the country is technologically superior and manufacturing chains are created locally can industries, such as hydrogen and solar, really stay in the country in the long term, he added. Haseloff warned against renegotiating the end-date of the coal phase-out after the Federal Constitutional Court has recently imposed stricter climate targets on the federal government. “Coal is set now,” he told MDR. “Anyone who questions that is shaking up our democracy.” To tackle the climate crisis, he said, emissions from heating and transport must be reduced instead.

Saxony-Anhalt is a very good example of the general conflicts we have to overcome on our way to climate neutrality. There are those who benefit from it and those who fear change.

In a party leaders’ debate on Monday, Green Party leader Cornelia Lüddemann said the funds should flow primarily towards renewable energies and climate protection, MDR writes. She emphasised the “huge opportunity” that the structural change with the coal phase-out offers Saxony-Anhalt and said renewable energies and associated storage technologies are the “job engine of the future.” AfD leader Oliver Kirchner, on the other hand, said that small and medium-sized businesses did not want to switch to renewable energies because it was too expensive. SPD leader Katja Pähle advocated for the creation of research and industrial jobs in the hydrogen industry.

Despite the state’s involvement in the coal industry, it has achieved its self-imposed emission reduction goal of staying under 31.3 million tonnes of CO2 emissions in 2020, media outlet Zeit reports. Saxony-Anhalt environment minister Claudia Dalbert (Greens) welcomed the result, but said achieving the goal was only an intermediate step. “In order to reach the new federal target of climate neutrality by 2045 at the latest, we have to increase the pace and save more CO2 even faster.”

However, climate protection does not seem to be a top priority for voters in the east German state. According to a recent survey, voters identify the coronavirus pandemic (39%), the economy (19%) and education (19%) as the most important political problems in Saxony-Anhalt. Environmental protection and climate change are in eighth place, with only six percent of voters saying that solving these issues should be prioritised in the state. On the national level, by comparison, nearly three-quarters of voters have identified climate policy as a decisive issue, saying it plays an important (32%) or very important (41%) role in deciding who to vote for, according a representative survey.

After visiting Saxony-Anhalt last weekend, CDU chancellor candidate Armin Laschet, who trails the Green Party leader Annalena Baerbock in nationwide popularity polls, told Deutschlandfunk: “The coal phase-out will have serious consequences in Saxony-Anhalt. New jobs will have to be created. There is also a protest potential that could elect populist parties.” He mentioned the billions of euros in support that would flow toward the state, saying “anyone who wants this to end successfully should not give his vote to populist, radical right-wing parties.”

The CDU in Saxony-Anhalt has received reproach for not distancing itself clearly enough from the AfD, with criticism also coming from CDU members themselves. The AfD currently polls at around 23 percent and has the potential to become the biggest party in the state. However, the conservatives stress that they rule out all cooperation with the populist party, as well as with the post-communist Left party, which polls at around 10 percent. “I have emphasised in no uncertain terms that under my leadership there will be no cooperation of any kind with the AfD and the Left, even after the state parliamentary elections,” said CDU state chair Sven Schulze to regional broadcaster MDR. In an interview with DeutschlandFunk, CDU chancellor candidate Laschet stated: “We do not want cooperation with the AfD at any level.”

The boost that the Green Party is experiencing on a national level is not leaving Saxony-Anhalt completely unstirred. During the previous state elections in 2016, the Greens had trouble getting over the five percent of the vote threshold needed to get into parliament. This time, polling at around nine percent, “it is not a question anymore whether they will get into parliament,” says Böcher. If they form a governing coalition with the CDU and the SPD again, they will be in a better position to push for a more ambitious climate policy since they come out as winners, Böcher says. He adds that the Greens could also manage to secure more than one ministerial position; they currently provide the environment minister.

The pro-business FDP party has also gained popularity, currently polling at around eight percent, whereas in the previous election they did not win any seats in parliament. Support for the Free Democrats has increased across the country and can mostly be attributed to their critical stance towards the government’s coronavirus pandemic measures – not to be confused with the AfD’s doubts about the pandemic itself –, Böcher explains. The SPD polls at around 10 percent, a similar result the party had five years ago. A repetition of the current ‘Kenya coalition’ is a likely outcome of the election, but the addition of the FDP could be necessary to create a majority – bringing along with it the many complexities of a four-party coalition, which would be a novelty in Germany on a state or national level.

In a state with a strong conservative and far-right voter demographic, there is also a progressive movement to be found mainly among young people in the state’s two main cities of Magdeburg and Halle. “Fridays for Future is surprisingly strong in Saxony-Anhalt,” says political scientist Böcher. “They are not just in Berlin, Hamburg or Cologne, where you would expect them to be.” On 29 May, a week before the state elections, climate activists from Fridays for Future joined the anti-racism alliance #Unteilbar and members of the service workers’ trade-union Ver.di for a demonstration in Halle calling for “social justice, climate justice, anti-racism, strengthening democracy and providing an alternative voice to the political (extreme) right.”

Böcher sees a strong divide between the population in the cities – where support for the Green Party is highest — and the many rural areas of Saxony-Anhalt. In previous years, Böcher says, many young and higher-educated people from rural areas have moved to the cities or to other federal states in Germany, leading to structural problems. “We have some winners and we have some losers of the changes. This leads to the difference in votes,” he says.

On a national level, the CDU is neck-and-neck in the polls with the Greens, with the former commanding around 25 percent of the vote and the latter around 24 percent. Since the last elections in 2017, the Greens have nearly doubled their votes, but the party has recently lost some of its momentum when its support declined for a second consecutive week. The SPD comes in third with around 15 percent of the vote – down from 22 in the last elections — followed by the FDP with 13 percent and the AfD with 11 percent.

The state elections in Saxony-Anhalt could also serve as an ‘alert’ for the CDU and the SPD, both of which seem to be losing votes on the state and federal levels, Böcher says. The strong voter support for the AfD on the one hand and the Greens on the other forces the two middle parties to reconsider their goals and clearly define the differences between them, Böcher explains. In an effort to attract voters in the federal elections, the parties can “learn from the Saxony-Anhalt elections.”