At the U.N. Climate Change Conference in Dubai last month, Japan announced that it would end the construction of coal plants without systems to capture their carbon emissions. This builds on Tokyo’s earlier move to join a Group of Seven commitment to largely decarbonize its power sector by 2035.

Yet JERA, Japan’s largest power producer and the world’s top buyer of liquified natural gas, is showing no signs of abandoning its fossil fuel-dominated business model. Rather, it is seeking to prolong the life of its coal-fired power plants through adopting unproven decarbonization technologies.

Without a change in corporate strategy geared toward a more aggressive deployment of proven, cost-effective renewables, JERA’s approach could derail Japan’s decarbonization goals and Asia’s shift to net zero more broadly.

JERA’s 2050 zero-carbon emissions roadmap focuses largely on decarbonizing its Japanese coal-fired power plants. While the plan includes the development of renewables, it lacks a specific target for domestic operations. JERA’s recent success in kickstarting 315 megawatts of offshore wind projects is promising, but clear, aggressive domestic deployment targets are needed to enable the company to contribute effectively to Japan’s decarbonization.

The company’s roadmap for decarbonizing its power-generating operations, which encompasses almost 60 gigawatts (GW) of thermal power capacity, includes plans to retire 1.4 GW of coal plants but hinges on a costly and likely ineffective strategy that will involve co-firing ammonia and hydrogen in the remaining units.

While demonstration projects are ongoing, commercial-scale deployment is set to occur incrementally, with ammonia and coal to be burned in a mix of 20/80 in all of JERA’s operating thermal units by 2030 and 50/50 within a few years after that. By 2050, those plants are supposed to be burning only ammonia. JERA’s gas units are to co-fire hydrogen in a 10/90 mix by the mid-2030s, meanwhile.

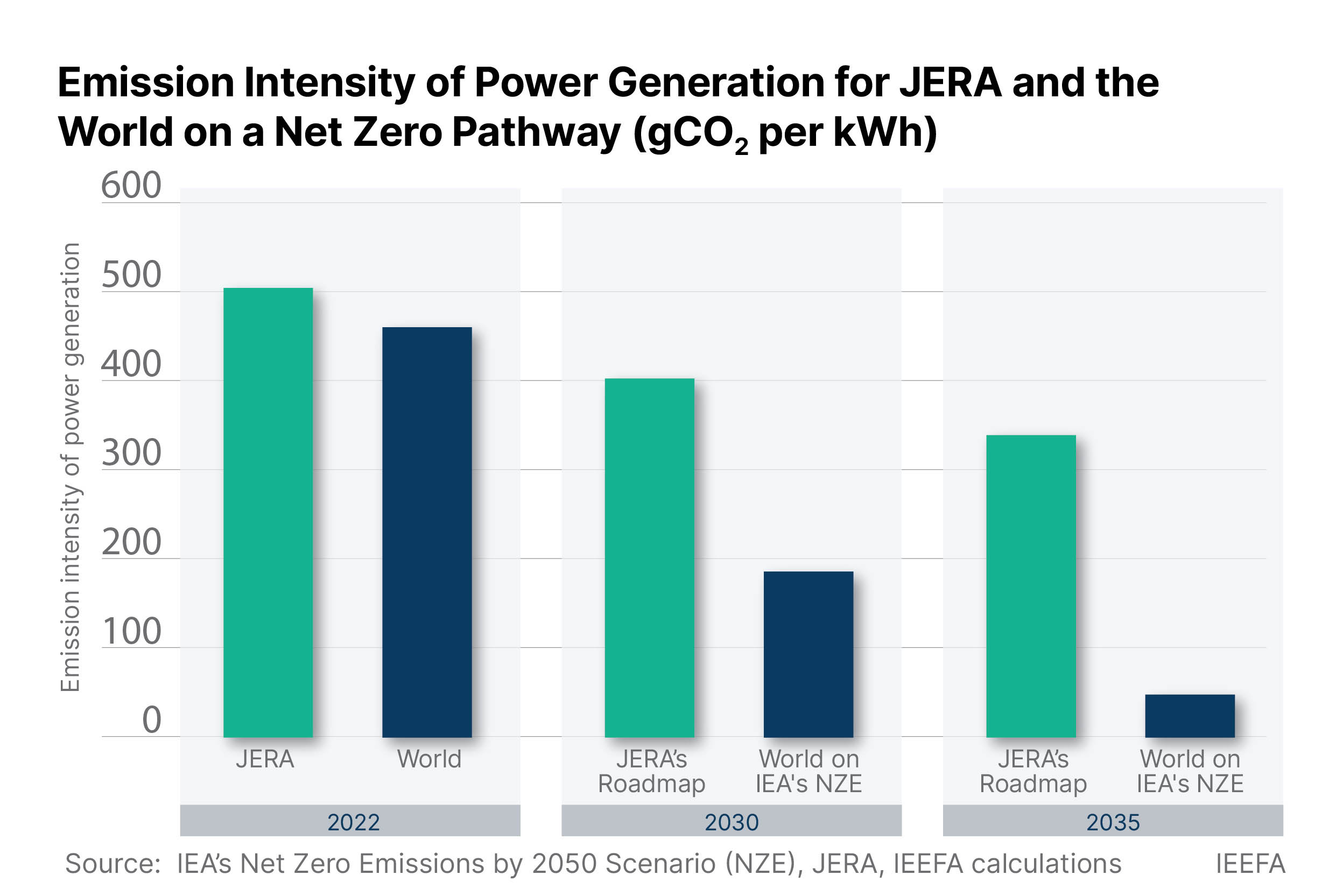

According to calculations by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, JERA’s roadmap would reduce the amount of carbon dioxide the company generates per unit of thermal power by a third by 2035 – progress, but far short of the net-zero path championed by the International Energy Agency.

Since JERA controls over a third of Japan’s thermal power capacity, its strategy would impede Japan from decarbonizing its power sector and delay necessary emission reductions.

JERA’s pathway will also likely cost the company more than investing in renewables would. Moreover, it relies on imports of hydrogen and ammonia, which will set back Japan’s energy security.

In addition, the co-firing of ammonia will produce nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas that would require expensive upgrades to capture. High rates of ammonia combustion by coal boilers have not been proven viable.

An examination of JERA’s assets and financial statements helps explain why the company is pursuing a strategy that could deliver Japan a costlier, less secure energy future.

First, the most profitable part of JERA’s business has typically been its domestic thermal power segment.

This business has commissioned several new coal and gas-fired units over the past two years. JERA last year estimated the average operating life of its coal and gas plants as 17 and 29 years, respectively. Co-firing ammonia and hydrogen will further extend the lifetime of these plants.

Second, JERA is a fossil fuel company by design, established in 2015 to consolidate the thermal generating assets and the fuel supply chains of Tokyo Electric Power Co. and Chubu Electric Power. The company’s fuel trading segment, JERA Global Markets, handles 12% of the global LNG market, providing it with considerable bargaining power to negotiate favorable contracting conditions.

Third, JERA’s overseas investments across the fossil fuel value chain complement and mitigate risks for its domestic operations. By developing demand and supply nodes around the world, JERA can optimize energy trading and shipping across its portfolio during periods of commodity price volatility so that higher input costs can be offset by trading gains.

With Japanese electricity demand in long-term decline at the same time that domestic nuclear power plants are being restarted, JERA is turning increasing attention to overseas markets.

Efforts are underway to cultivate ammonia and hydrogen use in the power sectors of Vietnam, Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, and Singapore. JERA executives are offering the false hope that Japan’s surplus LNG and its ammonia could help these countries decarbonize their power sectors.

JERA’s strategy does not fit easily with the commitment made at the Dubai conference by over 120 governments, including those of Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand, to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030.

By focusing on the preservation of its global fossil fuel portfolio, JERA risks delaying Japan’s energy transition and missing the opportunity to join the global shift toward renewable energy. While JERA provided Japan with solutions to its energy security challenges in the 2010s, the company needs to evolve to serve the emerging low-carbon economy.

Recentering JERA’s decarbonization roadmap around an accelerated deployment of renewables would help Japan and other Asian countries achieve their climate commitments, improve energy security, and reduce exposure to volatile fossil fuel markets. A strategic rethink could enable JERA to play a leading role in Asia’s energy transition.